As originally submitted and posted for CultKW on July 7, 2021.

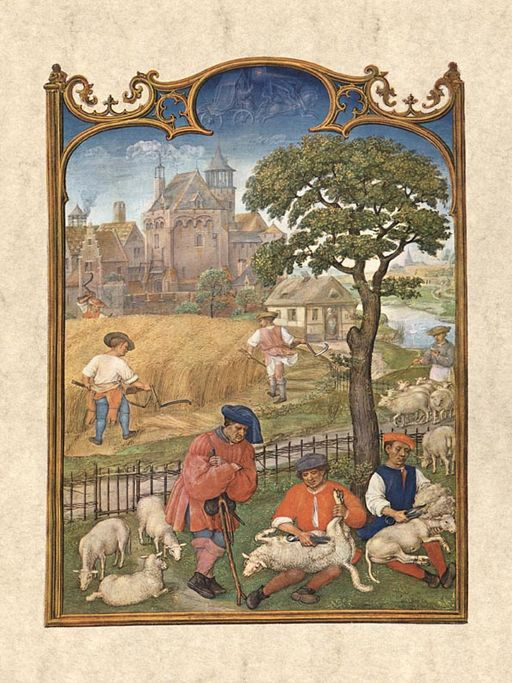

July, Brevarium Grimani, (Flemish, circa 1510) wikipedia

Here in Laurentian Ontario, the May “Two-Four” weekend is firmly established as a seasonal turning point, with emphasis on gardening, agriculture and outdoor recreation. I’d like to propose imagining the July First to Fourth stretch as a counterpoint, with emphasis on the various states, nations and federations on both sides of the long, traditionally peaceful border Canada shares with the U.S. of A.

Outrage

I spent a lot of my July First to Fourth this year online, furiously posting. It began with a response to a friend’s denunciation of what he saw as “deliberately timed vandalism in Victoria Park:” the pouring of blood-red paint over the statue of the park’s namesake monarch on Canada Day.

“I’m with you,” I wrote. “This is utterly deplorable. And, as we can see from some of the comments on your post, this isn’t going to stop.”

The incident happened a couple of blocks away from where I live, work and muse nowadays. I found some of the comments, on my friend’s wall and in other posts, terrifying. There are a disturbing number of voices who sound like they are ready to pull down all statuary, burn down churches, raze cemeteries, and hang the Pope for good measure.

This particular monument was erected in 1911, 10 years after the death of the Empress, in what was then still the Town of Berlin, Ontario. I’m not sure why I’ve grown so fond of it over the years. It is certainly not out of respect for the original purpose. On the contrary; what I find moving is how little remains of what I imagine those loyal, dutiful Daughters of the Empire had in mind when they decided to commission this work, and install it for posterity — i.e., for us.

I’ve suggested, in these musings, an adaptive re-use of the meaning of this and other remnants of empire and monarchy: They could have a fresh relevance, in Canada at least, as symbols of progress through peaceful transition. To me, they represent evolutionary adaptation, building on, with and through what exists. I prefer to treat them as symbols of what I hope is a rising spirit of “never demolish,” as opposed to the ceaseless disruption, erasure and destruction that has characterized British and U.S. Columbian culture and society since the days when Victoria ruled.

But, like words and storylines in general, such vestiges can mean whatever we choose. If people want to use these relics as a touchstone for a latter day “live free or die” revolutionary republicanism, that’s their prerogative.

Over and above whatever political meaning it may carry, the monument that was vandalized on Canada Day also has a more neutral aesthetic and cultural heritage value. It is an imposing presence, skillfully rendered in handsome bronze. The work has held up miraculously well over the years. But this artifact was not made to withstand willful destruction. It needs protection:

“It might be better,” I went on in my post, “if Cavaliere Raffaele Zaccaquini’s landmark sculpture of Victoria and the Lion were removed for safekeeping until the current beeldenstorm blows itself out. It is terrifying to see that it is even starting to take on some of the anti-Catholic zeal that drove my ancestors into such a frenzy during the original iconoclastic fury. After what happened last week [long story], I don’t trust the City of Kitchener with safeguarding heritage. Maybe this vulnerable, 110 year old public art work can be stored in the old armoury building in Galt, or the nearest pre-Confederation fort built to protect us from this kind of Boston Tea Party / Rebel Yell / Storming the Capitol red republican style of hooliganism.”

Inlaws and Outlaws

The assault on Victoria’s person cast in bronze was still on my mind three days later, when a friend and colleague sent me an early morning Independence Day greeting: “Happy July 4 if We were American.”

My first thought was:

“But we are American. We just didn’t take the separatist route. The proper way for a True North North American to observe July Fourth is to think lovingly of our long lost sibling, and promise not to be overcome with jealousy when the prodigal returns home”.

An hour or so later, I followed up with some additional thoughts:

“Ah, but it’s not so simple. We grew up and also left home eventually. The difference is that we have kept a loving, respectful relationship with the elders, despite how mean and cruel they have been known to be. We even keep celebrating great-great-great-great grandmother’s birthday, and smile in front of her tombstone in the park, regardless of how haughty, grumpy and humourless she could be, and how she never once came to visit us.”

The third installment gets darker:

“But that’s not really how it happened either, is it? Brother Sam and his Abrahamic brood returned home long ago. Or did we move in with them? I don’t remember exactly. Either way, where we live is actually nothing like a cosy family home. It is more like a vast ranch. A plantation, you might say. With mines and oil wells scattered among the cotton, tobacco and indigo fields. Together, we’ve built a family business empire with a global reach. The sun never sets on our domains. The meanness, the cruelty aren’t just a quirk among the old and frail. It’s a family trait. We share a special talent, a gift, for theft, fraud, murder, subjugation, plunder and rapine.

Two or Three Trains Running

I’d written a gentler version of the same story the day before, inadvertently on another friend’s timeline, something you should only do when you’re sure the imposition is welcome. In this case, I’m not sure.

This version of the tale began as a response to a Canada Day reflection on the “colonial train” we’ve all been riding on since 1867. My friend’s words were thoughtful, compassionate, hopeful: It was about how we are moving forward to something better. .

“Love the train metaphor,” I answered. “I agree, there is no going back. Living is forward motion. My version of the story (which I’d recently summarized on my personal website) varies slightly. It might not be a truer picture, but it helps me keep my hopes up. In my telling, it goes something like this:

In Canada, it is actually the independence train that has been running for 154 years. Similarly, in the U.S. it’s the Settler Home Rule Express that has been in operation for 245 years now. Both trains are sleek, modern, efficient. Both have, until recently, been steadily accelerating.

These national railways carry almost all the wealth, power, glory and influence that exist in their respective territories. And they’re intricately segregated according to class, occupation, age, education, race, ethnicity, language, accent, religion, tastes, preferences, proclivities, etc., etc. There are passenger cars, sleeper cars, dining cars, freight cars, coal cars, tanker cars, and even “concentration” cars full of people who have been forced to come along for the ride.

Both trains were built to run over everything that lies in their paths. They’ve become a danger to the very ground we live on. Mercifully, these parallel state railway operations appear to be slowing down. The view out the window isn’t as blurry as it was a while ago.

We, the living, are the paying passengers. And we are actually in charge. We just don’t seem to realize it yet. We appear to be unaware that if we want to stop this juggernaut, and change its purpose and direction, all we have to do is pull the emergency cord and reset the controls.

We don’t have to blow anything up, hunt down the owners and the management, or hang the conductor, the brakeperson and the engineer. We just have to make some adjustments.

But there are certain interests and mindsets who feel threatened by passenger rights, freedoms and powers, especially the freedom to associate. And they’re doing everything they can to keep us distracted, confused and anxious. Above all, they want to keep us divided.

In my story, there is also a colonial/imperial train that has been chugging along for 529 years. It is ludicrously old-fashioned, rickety and slow. It still carries negligible quantities of wealth and glory, but no real power or influence. The freight it carries is mostly antiques, souvenirs, mementos, curios, bundles of paper, fading photographs, rusty statues and other such bric a brac.

There are a few living humans on board, oddly attired with crowns, jewels, sceptres, swords, sashes, garters and such. For the most part, however, this is a train filled with ghosts, skeletons and crematorium ashes. No one is in charge. We have no power or influence there. But that’s not a problem: This train will come to a halt on its own accord. I suggest we let it rest in peace.”

Epilogue

There, I’ve had my say for another July First to Fourth season of nationalist and federalist celebration and contemplation.

I don’t really expect to win anyone over to my peculiar way of telling the story, nor do I care very much if people choose to carry on with what looks to me like battling ghosts and skeletons.

But I do want to make it clear that, by looking for alternatives to words like “colonialism” and “decolonization” when discussing the challenges before us, and by smiling a little when I look up, way up, to that bronze memorial to the Empress Victoria around the corner, I’m not signalling that I’ve gone over to the dark side.

There are no sides. Fear, hate and resentment are not forces to be reckoned with, tit for tat. They are an emptiness that begs to be filled, a void that is ready for light.

Ringo Starr, who turns 81 today, has the right idea: Peace and love, that’s about all there is to it. Here’s a personage whose radiant influence over the years may well have exceeded that of the Empress Victoria at the apex of her glory. The former Beatle doesn’t live in England anymore, so his “peace and love” birthday wish is actually California dreaming. Well, God save Ringo. Long may he shine.

Ringo Starr’s public art installation; image via Beverly Hills Police Department

The Tusculum portrait, a marble sculpture of Julius Caesar. wikipedia

P.S.: An anti-imperial, decolonizing afterthought

With all this purging, purifying, renaming and graven image smashing going on, why do we remain so content with carrying on with the ancient practice of naming two full months, ⅙ of the days of our lives, after two of the most notorious dictators, conquerers, colonizers, prison builders, slave hunters, culture destroyers and heaven stormers of all time?

To quote another California dreamer, in this case an early adopter of the inter-planetary fantasies of Elon Musk (“Hijack the Starship”):

Two thousand years

Two thousand years

Two thousand years

Of your Goddamn Glory*

If anyone wants to pour red paint over the memory and legacies of Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus, I wouldn’t utter a peep.

If someone were inspired to lead a march to restore a pacific, decolonized Quintilis and Mensis Sextilis to the contemporary summer calendar, I may join the procession.